This essay was originally published on my (now-defunct) Substack newsletter on 14/12/23.

Doctor Who: The Complete History – Issue 41 / Volume 32 contains an embarrassing error. If you would be so kind as to take down your personal copy off the bookshelf behind you, which I’m sure you all have, open it and turn to page 69. You will see the following two sentences about halfway down the page:

“Another alteration was to change the name of the object from the Pentagram to the Dodecahedron. A five-sided object was thought not entirely practical as a geometric shape, whereas the 20-sided structure was more effective and still incorporated pentagrams in its faces…” (emphasis mine)

I don’t know about you, but I’m furious.

Absolutely furious, I tell you.

Is nobody interested in mathematical literacy?

A dodecahedron – as I’m sure we all know – has twelve sides, not twenty. The Greek prefix ‘dodeca-’ literally means twelve! We should all be fluent in Greek by now or else we wouldn’t have spotted that Professor Carl Thascalos in The Time Monster was none other than the Master!

I personally feel that the Dodecahedron warrants a bit more discussion than it actually gets among Doctor Who critics. It’s probably because they probably don’t like writing about maths, isn’t it? Or perhaps it’s because they know that their audience don’t like reading about maths? I mean, that’s what my DMs over the past few months are telling me. Or maybe it’s because people don’t like thinking about Meglos? Poor Meglos.

But don’t worry. I’ve not come to praise Meglos; I’ve come to bury it.

During the development of their scripts for Meglos, writers John Flanagan and Andrew McCulloch considered a number of titles for the serial [1]. These included ‘The Golden Star,’ ‘The Golden Pentangle,’ and possibly, ‘The Golden Pentagram.’ We can sense a bit of a theme going on with these titles; it’s all about the number five. The Greek prefix ‘pent-’ means five, after all. Flanagan and McCulloch’s original idea was to have The Pentagram as the mystical source of power for the planet Tigella. A pentagram is a five-pointed star that has symbolic links to the societies of Ancient Greece.

There would also be two groups of people, the scientific Savants and the religious Deons, who would argue over the meaning of The Pentagram. The Savants understood The Pentagram to be a powerful source of energy whilst the Deons viewed The Pentagram for what it represented, a powerful occult symbol that they could worship. The cliché of clashing scientific (i.e. rational) thinking and religious (i.e. superstitious) thinking had been previously used in Doctor Who by this point, most notably in The Daemons [2] and The Masque of Mandragora.

So how did they end up shifting from a five-sided shape to a twelve-sided solid? That’s all down to the script editor, Christopher H. Bidmead.

It was the more mathematically-literate Bidmead who changed the mystical power source of The Pentagram into The Dodecahedron, as he thought this would be more practical and effective on-screen. The dodecahedron is a twelve-sided shape, where each face is a regular pentagon. Honestly, it’s an inspired choice. It’s just a shame that the decision to move from a two-dimensional shape to a three-dimensional solid doesn’t actually help add any depth to the scripts of Meglos; it remains a rather flat story. But, thanks to The Dodecahedron, we can at least pull out some neat symbolism.

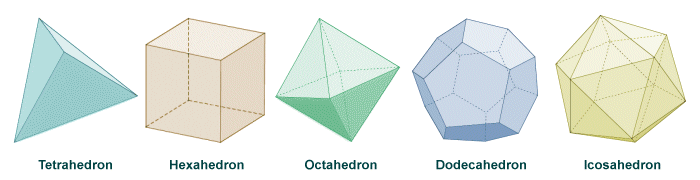

The dodecahedron belongs to a select group of mathematical objects known as the Platonic solids. Why are they named after Plato (c.427 – c.347 BCE)? Don’t worry about that for now, we’ll come full circle at the end. Now a Platonic solid is defined as a regular, convex polyhedron (in three-dimensional space). Don’t panic, I’m going to break this down. What this simply means is that it is a three-dimensional solid – pause – where every side and every angle are the same – pause again – and every face of the solid is a regular-sided polygon. Okay, look, if that was too many words for you then do not fear, for I have a picture. You like pictures, don’t you?

There are only five Platonic solids:

- The tetrahedron (four-sided, made of triangles)

- The hexahedron (six-sided, made of squares, aka ‘the cube’)

- The octahedron (eight-sided, also made of triangles)

- The dodecahedron (twelve-sided, made of pentagons)

- The icosahedron (twenty-sided, also made of triangles)

So not only did Bidmead pick a solid made up of five-sided shapes, he also picked a solid from an exclusive group of five mathematical objects. He probably though Platonic solids were interesting because of their perfect symmetry. Twist it, roll it, flip it, bop it – they’ll always look exactly the same once you pop them back down in the exact same spot as they started. The mathematician Euclid (c.325 – c.270 BCE), known as the “father of geometry,” proved that there are only five Platonic solids in the final proof of his magnum opus, The Elements.

Platonic solids also known in some parts as Pythagorean solids. You remember Pythagoras (c.570 – c.490 BCE) from school, right? Weird fella, had his own cult. Anyway, the concept of Platonic solids actually pre-dates the Ancient Greeks entirely; there’s evidence that they can be traced back to earlier civilisations, such as the Ancient Egyptians and Sumarians.

If you’re a fan of board or role-playing games, you will recognise these as the common shapes of dice used when playing. Their natural geometric properties make them ideal for games involving chance, allowing the probability of rolling each number to be equally likely. They’re also just quite aesthetically pleasing to look at.

I’ve demonstrated why the dodecahedron is a mathematically (i.e. scientifically) interesting shape; I’m sure the Savants among you will be delighted. But what about the Deons? Is there something that’s symbolically (i.e. religiously) interesting about the dodecahedron?

Yes, there is!

And that’s why I think, on this particular aspect, it was a shrewd choice by Bidmead.

The group of Platonic solids are recognised by several cultures throughout history as having ‘divine’ properties. The five Platonic solids were believed to represent the four major elements and the universe:

- The tetrahedron represents fire

- The cube represents earth

- The octahedron represents air

- The icosahedron represents water

- And the dodecahedron represents the aether that holds the universe together [3].

This can be traced back to Plato’s Timaeus, a dialogue in which he outlines his beliefs about the existence of the universe. It is the first written record of the existence of these solids; hence why they are named after him. Plato believed that these five solids “were so fundamental that they form the very building blocks of matter itself [4].” Moreover, Plato believed that the God who created the universe was a mathematician who used the shape of the dodecahedron for ‘arranging the constellation of the whole universe [5].’ So there, the dodecahedron does legitimately have symbolic power; Plato has woven it into his own highly influential creation story for the universe.

Okay then, but here’s the wildest part. Back in 2003, a group of scientific researchers actually proposed that the shape of the universe… is a dodecahedron! Maybe there’s hope that the Savants and the Deons will find harmony in their opposing viewpoints one day…

So wait, hang on a moment… If Meglos is trying to steal The Dodecahedron, and that object is believed to represent the entire universe then that would mean, in a purely symbolic sense, that Meglos is… trying to take over the universe!

Surely not?

I mean, who would enjoy watching a Doctor Who story about a shape-shifting alien with ambitions of taking control of the universe using the power created by a Platonic solid?

MEGLOS: Hello, Tigella! Who takes the Dodecahedron takes the Universe! But, bad news everyone! Because guess who? Ha!”

Now that might just be the funniest thing from the entirety of Meglos.

>

Footnotes

[1] All references to the pre-production history of Meglos are taken from Doctor Who: The Complete History – Issue 41 / Volume 32, p65-71.

[2] I wonder what then-Executive Producer Barry Letts thought of Meglos, given he was an uncredited co-writer of The Daemons?

[3] Alex’s Adventures in Numberland by Alex Bellos, p92-93.

[4] Quoted from Finding Moonshine by Marcus du Sautoy, p59.

[5] Finding Moonshine by Marcus du Sautoy, p59.

Leave a comment