This essay was originally published on my (now-defunct) Substack newsletter on 07/12/23.

Right at the start of The Star Beast, did you notice that the Doctor unstacks and then restacks a set of three cardboard boxes, arranged in size order, largest at the bottom and smallest at the top, being carried by Donna Noble? Funny that, because that sounds remarkably similar to a game that the Doctor once played before with a character known as the Toymaker.

The Toymaker, played by Neil Patrick Harris, is due to return this Saturday in The Giggle, but he hasn’t been seen on screen since his debut in 1966’s The Celestial Toymaker, then played by Michael Gough. During this adventure, the First Doctor is separated from his companions, Steven and Dodo, and forced to play a mathematical puzzle called the Trilogic Game. He also gets turned invisible, and then muted by the Toymaker, just for his own amusement, and definitely not because Hartnell was taking some time off for holiday/health reasons. It would be a little remiss of me not to take a quick gander into one of Doctor Who’s earliest forays into recreational mathematics.

The Trilogic Game is a variation of the Tower of Hanoi puzzle that was invited by the French mathematician Édouard Lucas (1842-1891) in 1883. Script editor Donald Tosh decided to add the puzzle to the serial, building upon the original storyline set out by credited writer Brian Hayles [1]. There are a number of other names given to this such as the ‘Benares Temple’, the ‘Tower of Brahma’, or even just ‘pyramid puzzle’. There’s an air of exoticism/mysticism about all these names, but we will get back round to that. We should probably establish what the game is first.

The game consists of three rods. On the first rod, a number of discs (we will call this n) are stacked in size order. The second and third rods are empty. Your objective is to ultimately move the entire stack of discs in size order from the first rod to the third rod. But you must obey the following rules:

- You can only move one disc at a time.

- Each move consists of moving the top disc from the stack on any rod.

- No disk may be placed on top of a disc that is smaller than itself.

The minimum number of moves required to solve the puzzle is 2n – 1, with n being the number of discs. (So, for 3 discs, the minimum number of moves is 23 – 1 = 8 – 1 = 7.)

It’s a fairly iconic form of maths puzzle – you’ve probably seen in some form like in a toy shop or in a book somewhere. My earliest memory of this type of puzzle comes in the form of ‘Puzzle No. 6 – Piles of Pancakes 1’ in the 2009 Nintendo DS video game Professor Layton and Pandora’s Box (or Professor Layton and the Diabolical Box if you’re from North America… have you folk just never heard of Pandora?).

The number of moves is also a point of interest. Any number of the form 2n – 1 is known as a Mersenne number, named after the French polymath Marin Mersenne (1588 – 1648). They’re useful to know in computing since they give the upper bound for a given number of binary switches before circling back round to zero (22 – 1 = 3 for two switches, 23 – 1 = 7 for three switches, 24 – 1 = 15 for four switches, and so on…)

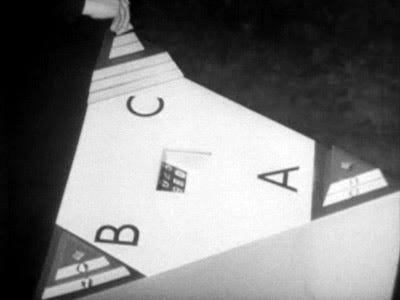

In The Celestial Toymaker, the Toymaker gives the Doctor only 1023 moves to finish the Trilogic game, or else he would be trapped in the Celestial Toyroom forever. Using our newfound knowledge of Mersenne numbers, we can spot that 1023 = 210 – 1, which means the Trilogic Game must have ten pieces. Sure enough, there are ten pieces visible on the game board in the surviving material from this serial. It’s just that logical when you think about it.

I mentioned earlier that the Tower of Hanoi puzzle was actually invented by a French mathematician called Édouard Lucas in 1883. Yet the puzzle itself has a popular association with East Asia, and this association prompted the production team to depict the Toymaker in the garb of a Chinese mandarin [2]. Thankfully, this has (as far as I can tell) been dropped in the Toymaker’s return appearance. But if the puzzle itself doesn’t come from East Asia, then how did the association occur in the first place?

In a nutshell, some people started telling very tall tales and the fabricated myths stuck around. There are several variations of the myth, but the essential story, in my own words here, was this [3]:

‘Somewhere there’s a temple in an ancient city in Vietnam, or possibly India. Within that temple, a group of monks have to move a pile of 64 sacred discs from one location to another. The discs are very fragile, so only one can be carried at a time. A larger disc may not be placed on top of a smaller disc or else it will break. There are only three locations in the temple where the discs can be placed: the starting location, the destination location, and one other location.’

You might be thinking this sounds somewhat familiar? You’re right!

It’s the same rules and conditions as mentioned earlier. Just now, they’ve been turned into a story. It’s funny, there’s probably a lot of writers out there who don’t like maths. And yet, if there’s one thing mathematics and writing have in common, it’s problem-solving. Perhaps maths and stories are not too dissimilar after all?

But wait, there’s one more piece to this legend.

‘The legend states that, before the monks make the final move to complete the new pile in the new location, the temple will turn to dust and the world will end.’

This aspect of the Tower of Hanoi myth is also reflected within the televised serial. The Doctor hesitates to make the last move of the Trilogic Game because the Toymaker warns him that the entire realm in which they exist will be destroyed upon its completion. The Toymaker will live on, the Doctor and his companions will not.

You might find this incredible to believe, but The Final Test actually makes an appearance in an academic maths textbook on the Tower of Hanoi puzzle. Behold!

“These events have already been anticipated in 1966 at precisely 21 minutes and 33 seconds into the fourth part, called The Final Test, of the episode The Celestial Toymaker from the British science fiction television series Doctor Who. This is the moment when the First Doctor in his 1023rd move (optimally) finishes the classical three-peg [Tower of Hanoi] with 10 discs, named the Trilogic game in this story. Luckily for us, with the last move the Doctor only destroys the world of Toymaker, whereas he himself and his two companions manage to escape the vanishing world with the time machine TARDIS.”

I just think it’s really wild that a 1966 episode of TV’s Doctor Who actually features in a serious academic maths textbook [4].

Anyway, the Doctor manages to escape the Toymaker by impersonating his voice from inside the TARDIS, allowing them to get away unharmed. And so, the legend is finally completed: the Toymaker’s realm was destroyed. Doctor Who really brought about the end of the world.

Perhaps that is why the Toymaker has ventured to planet Earth this time – to put the Doctor’s honorary home-world at stake instead? To bring about the end of the world? Nay, the end of the universe?

Can we expect some more mathematical games to feature in The Giggle?

Will a change in the Doctor’s voice prove decisive in vanquishing the Toymaker once again?

And what will the Fourteenth Doctor’s last move be?

“Make your last move, Doctor. Make you last move.”

>

Footnotes

[1] Serial Y: The Celestial Toymaker by Shannon Patrick Sullivan.

[2] I’ve borrowed this observation from James Cooray Smith’s incredibly thorough piece on The Celestial Toymaker. You can read it here on Buttondown.

[3] There are multiple versions using various wordings for this fabricated monomyth but I’ve used the one here from the University of Toronto Math Network as a rough basis.

[4] If, like me, you actually want to read this textbook, it’s available here on the Internet Archive here.

Leave a comment