On the 27th of February 1987, Sylvester McCoy was announced as the new Doctor. He would play the seventh then-known incarnation of the Time Lord, and so henceforth he would be referred to as the Seventh Doctor. Keen fans of Doctor Who (yes, that means you reading this right now) know that this rule of logic doesn’t last for long in the show’s 21st century revival. Shortly after this announcement, McCoy would begin filming his debut serial, Time and the Rani (1987).

There are several notable firsts in Time and the Rani. Besides being the first appearance of McCoy, Time and the Rani would also be the first story (of twelve) to be script-edited by Andrew Cartmel, the first (of two) to be directed by Andrew Morgan and the first to debut a brand-new, fully-CGI title sequence, designed by Oliver Elms (his only one), with a brand-new arrangement of the iconic theme tune. The serial is also the first (of six) to be scored by composer Keff McCulloch, who would go on to score half of the McCoy era serials as well as the 1992 VHS release of Shada and the 1993 Children in Need special Dimensions in Time.

There are also several notable lasts in Time and the Rani. It would be the last (of four) Doctor Who serials written or co-written by Pip & Jane Baker. Like ‘em or loathe ‘em, Pip & Jane Baker are nevertheless two of the most prolific writers in 1980s Who, second only to Robert Holmes in terms of number of writing credits. In fact, given that Part One of ‘The Ultimate Foe’ (The Trial of a Time Lord (1986) Parts 13-14) was ostensibly written by Eric Saward in his capacity as then-script editor, rather than as credited on-screen by Robert Holmes, the Bakers would have been able to claim that they were the most prolific writers for the Sixth Doctor, as played by Colin Baker, were it not for the undeniable fact that Holmes had penned a three-part Season 22 serial (a six-parter if you’re dealing in old money) compared to their own measly two-part Season 22 serial (a four-parter in old money). Indeed, there were serious plans to have this story be the last Doctor Who serial for Colin Baker, which would have ended with his regeneration into McCoy.

It is also the last appearance (of two) for the Rani as played by Kate O’Mara, non-canonical Children in Need specials notwithstanding. The Rani is a renegade Time Lord, like the Doctor or the Master, who is an amoral scientific genius who likes to conduct cruel and unusual research experiments. Some commentators have noted that the Rani has some shared characteristics with Margeret Thatcher, the then-incumbent Prime Minister, who was notably a chemist before entering politics and was particularly known for her unsympathetic and uncompromising demeanor, hence her popular nickname The Iron Lady. 1987 would see her last election victory (of three) before ultimately being ousted by her own party in 1990, just under a year after the Seventh Doctor and Ace set off into the sunset to complete whatever ‘work’ they needed to do. (There’s also a sad parallel here for Colin Baker, who was ultimately ousted from the lead role by his own producer.)

Such firsts and lasts are probably well-known to Doctor Who fans who are all clued up on their production trivia and so, as a natural consequence, spend lots of their time writing copious books, blog posts and magazine articles so that they can subject other Doctor Who fans to all the production trivia which they have clued themselves up on. But there’s also another first and last within the serial that has not been cause for much remark, and that’s probably down to the fandom’s lack of knowledge on the history of mathematics as well as her relative obscurity. Because of course, Time and the Rani marks the first, and indeed last, appearance in the 20th Century iteration of televised Doctor Who (i.e. the Classic Who era) of a real-life female mathematician: Hypatia.

As a consequence of her relative obscurity, we know fairly little about Hypatia, but in fairness she did die over 1600 years ago, which has been one of the main impediments on our ability to find things out about her. Hypatia (c.350-370 – March 415) was a mathematician, philosopher and astronomer; she is primarily known as the first woman to make a substantial contribution to the development of the field of mathematics. Her most notable works are commentaries on the works of Apollonius (who wrote on geometry) and Diophantus (who wrote on number theory), but she doesn’t have any known original works. This aspect has a disappointing parallel with that of Ada Lovelace, a female mathematician, and arguably the first computer scientist, who is primarily known for her own commentary on the workings of Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine. Lovelace, Babbage and the Analytical Engine all feature in the episode Spyfall: Part Two (2020). Incidentally, Lovelace would become the first real-life female mathematician to appear in the 21st Century iteration of televised Doctor Who (i.e. the New Who era). I think we all hope she won’t be the last.

Hypatia’s appearance in Time and the Rani is also really brief. So brief in fact that when I sat down to watch the serial so that I could take some screenshots of her really brief appearance I actually completely missed her on the first pass. It also doesn’t help that I was actively looking for someone dressed in a traditional white Greek toga, thinking this would be an easily identifiable way for the costume designer to signal ‘Greek philosopher’ to the audience; her outfit within the serial is still toga-like but has darker colours and an elaborate headpiece of some sort. But nevertheless, she gets a namedrop from Mel in the same breath as Albert Einstein. Beyus somewhat amusingly retorts with “Names which are meaningless to us.” It is reasonable to believe that Beyus, an alien from a far-off planet, wouldn’t know either of these human geniuses. Whereas for the audience at home, they will have almost certainly heard of Einstein, but would find the name of Hypatia just as meaningless as Beyus. We can reasonably attribute the selection of her appearance to the eccentricities and learnedness of the Bakers. But as the Doctor states, they are both “Geniuses,” and quite rightly too.

I feel that we cannot overlook the coincidence that the first female mathematician from history to appear in televised Doctor Who features in a serial co-written by a female writer. And not just any female writer, but the most prolific female writer Doctor Who has ever had to-date; no other woman has received credit for writing four Doctor Who stories, nor more than c.320 minutes of screentime. Jane Baker has never shied away from increasing the prominence of female characters within her stories. She was the co-creator of the Rani, the only female villain to have a recurring appearance in 20th Century Doctor Who. Her name even features in both of the titles of the serials in which she appears; the Master has never had any such luck.

We can even see this attention in the less prominent characters as well, for example the wives and mothers of the miners disappeared by the Rani in The Mark of the Rani (1985). The likely existence of such characters would usually be rendered invisible, completely ignored altogether, in many earlier Doctor Who stories. But here we see these woman asking Lord Ravensworth where they have gone and then later on weeping in the background, reminding us that the loss of these men is tragic within the scope of their lives, and not just familiar cannon fodder for the Villain of the Week™. Such consideration for the impact on the lives of the family and friends of a character who gets bumped off by a monster or villain is a much more common occurrence within the 21st Century iteration of the show. As much as the Bakers get criticism for their scripts being old-fashioned and overly loquacious, they still brought some pretty good ideas to the table. Now I’m not saying that they invented female representation in Doctor Who (and neither did Steven Moffat for that matter!), but they certainly got the ball rolling, and for that some credit is most definitely due.

One person who evidently learnt something from their work was none other than Chris Chibnall. As I’m sure you are aware, Chris Chibnall is perhaps best known to Doctor Who fans as that guy who once appeared on national television to criticise Pip and Jane Baker’s work on Doctor Who in the guise of a Doctor Who fan. Other minor biographical details include that he was the showrunner of Doctor Who from 2018-2022 and penned the aforementioned Spyfall: Part Two, which features Ada Lovelace, the next real-life female mathematician to appear in Doctor Who, as well as the Thirteenth Doctor of course, the first female incarnation of the Time Lord. It would therefore seem that Chris Chibnall has now decided that Pip and Jane Baker may have had some good ideas after all.

My only real critique of the Bakers introducing Hypatia to over five million viewers at home is that Hypatia didn’t get one single line of dialogue, nor even a single stage direction, meaning she’s still largely overshadowed by the more prominently featured Einstein. The Bakers have managed the low bar of including a woman in STEM but not the adjacent equally low bar of having her talk. Chibnall surpasses this by having Lovelace not only speak, but play an integral part in a story which is in part about the power of computing technology. But Lovelace regrettably lacks agency in her own narrative in Spyfall: Part Two, something that Chibnall has yet to learn, and something that we will have to address another time in another blog.

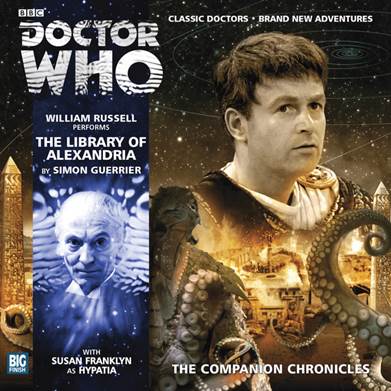

Thankfully, Hypatia gets ample dialogue, and even a namedrop on the cover of a rather good Big Finish audio play within the Companion Chronicles series called The Library of Alexandria, penned by Simon Guerrier. I respect Simon Guerrier for putting in the occasional dose of maths and science within his Doctor Who stories, and he even co-wrote the book The Scientific Secrets of Doctor Who with Dr. Marek Kukula. The story sees the First Doctor alongside Ian, Barbara and Susan journey back to the 5th Century to appreciate the magnificent Library of Alexandria, only to be embroiled in events that ultimately lead to its destruction, as the Web of Time dictates must always happen. Ian, who is a science teacher, befriends Hypatia over the course of the story. Meanwhile, Barbara and Susan to rescue several books from being burnt within the library by bringing them into the TARDIS, rescuing knowledge that would have otherwise been lost to history, and the Doctor helps some children create what would later be known as the Rosetta stone, paving the way for future translations of ancient works. It’s nice to see that no matter wherever Doctor Who is in time and space, it’s always there to teach us something new.

Next month: Chris Chibnall is an absolute blockhead!

Leave a comment