“Saving the day through a heartfelt sing song and the illogical powers of an emotional leaf felt like a distinct cop-out.” – Mark Snow, IGN.

“I caught the sound of a man airing the preposterous notion that the sum of all primes approaches infinity.” – A complaint to BBC Radio 4 regarding an episode of More or Less.

Infinity makes people cross. The very idea asks us to the imagine the most incredible thing, that something can go on forever. Now Doctor Who fans are likely to say that this is a show that will ‘go on forever’ but what they actually mean is ‘Doctor Who will go on for the rest of my life and for many years after.’ If Doctor Whowere to indeed run for, say, 100,000 years then that would seem like a hell of a long time. But personally I think Doctor Who is a hell of a show. However, 100,000 years is just the teeniest, tiniest drop in the ocean when compared with infinity.

How then can we begin to comprehend something like infinity when we only have a finite lived experience to compare it with? When presented with entirely logical arguments on the consequences of infinity, why do we intuitively decide to reject these as preposterous and absurd? Perhaps it’s because it’s unlike anything else we know. Perhaps it has something to do we how we feel about infinity instead. I’m hoping to shed some light on the mysteries of infinity itself, and we can do so using one of the more underrated episodes in Doctor Who’s history: The Rings of Akhaten.

Based solely on the 2014 Readers’ Poll conducted by Doctor Who Magazine, it would seem that The Rings of Akhaten is one of the most unpopular episodes among the fandom at-large. It languishes at ninth from the bottom. A subsequent poll done in 2023 saw it rise by five places within a ranking of just the Eleventh Doctor episodes, but that’s still not a massive improvement.

Writer and fan critic William Shaw investigates the fan reception to the episode within his Black Archive entry on The Rings of Akhaten. Shaw observes that practically all of the contemporary reviews of the episode were actually quite positive, or only mildly negative. Only Doctor Who Magazine published a strongly negative review of the episode around the time of broadcast. So why has this hit differently with the ‘hardcore’ Doctor Who fans? One of the main critiques is the episode’s climax, which not only involves the notion of infinity but also what IGN’s Mark Snow has described as “the illogical powers of an emotional leaf.”

CLARA: I brought something for you. This. The most important leaf in human history. The most important leaf in human history. It’s full of stories, full of history. And full of a future that never got lived. Days that should have been that never were. Passed on to me. This leaf isn’t just the past, it’s a whole future that never happened. There are billions and millions of unlived days for every day we live. An infinity. All the days that never came. And these are all my mum’s.

Upon Clara’s successful resolution to the problem at hand, the Doctor decides to come back to the fore and act like he knew this was the answer all the time.

DOCTOR: Well, come on then. Eat up. Are you full? I expect so, because there’s quite a difference, isn’t there, between what was and what should have been. There’s an awful lot of one, but there’s an infinity of the other. And infinity’s too much, even for your appetite.

This dialogue poses a number of rather intriguing questions. Are the Doctor’s past memories merely finite in size? Are the lost future days of Clara’s mum, symbolised by the most important leaf in human history, really of an infinite magnitude? Are we supposed to just accept that the unlived lifetime of Clara’s mum is infinitely more complex than that of the Doctor’s past? What makes this even more unintuitive and radical a conclusion to the story here is that we perceive the Doctor as this immortal hero, who stars in a show that is built to go on forever.

Why don’t we take a brief look at the history of infinity and see if it can tell us anything?

The earliest recorded mention of infinity is widely regarded to be attributed to the philosopher Anaximander (c.610-546 BC). He used the word ‘apeiron’ which means “unbounded” or “indefinite”, though philosophers such as Heidegger and Derrida have debated the translation of this term. However, the Ancient Greeks were terrified by the notion, a fear now termed as a “horror of the infinite.” This is especially noticeable in the works of Euclid who was the first to prove the existence of infinitely many prime numbers, and yet he consciously avoids using the word ‘infinite’ altogether. Instead, his proof in Book IX of The Elements translates into English as “Prime numbers are more than any assigned multitude of prime numbers.” The Ancient Greeks may well have been among the first people to entertain the notion of infinity, but they refused to take it seriously.

Arguably the most well-known use of the infinite in philosophical pop culture is Zeno’s Paradox about a hypothetical race between the hero Achilles and a tortoise. The tortoise is given a head start on Achilles and the race begins. By the time Achilles has reached the starting position of the tortoise, the tortoise has moved some distance ahead. Once Achilles has reached that position, the tortoise will have moved ahead some more, albeit a shorter distance. This process continues ad infinitum, and so the argument here is that Achilles will never overtake the tortoise to win the race. Intuitively though, we know in the real world that a man would easily overtake a tortoise in a running race, and herein lies the paradox. What makes this paradox of infinity somewhat inadequate is that it does not explicitly recognise that an infinite sequence of events can still lead to a finite result. This is the entirely logical result of summing up a sequence of numbers that converge towards a certain value. In mathematics, we call this a limit.

Infinity, however, was still slow to catch on in the minds of mathematicians and doesn’t get its iconic ‘figure-of-eight’ symbol (∞) until 1665 when John Wallis first described an infinitesimal as the fraction 1/∞. His idea caught on with the likes of Newton and Leibniz who would go onto independently discover calculus (formerly known as infinitesimal calculus) during the latter half of the 17th Century. But it wasn’t until the end of the 19th century when infinity finally found its biggest supporters. Like it or not, Infinity was here to stay.

Georg Cantor (1845 – 1918) introduced the radical new notion of cardinality, a way to count the magnitudes of infinity. Rather than treat infinity as some flimsy piece of philosophical conjecture, Cantor decided that infinity should now be regarded as an entirely separate concept with its own set of rules. Some of his contemporaries really did not like this idea and some even went as far as to describe this as “heretical.”

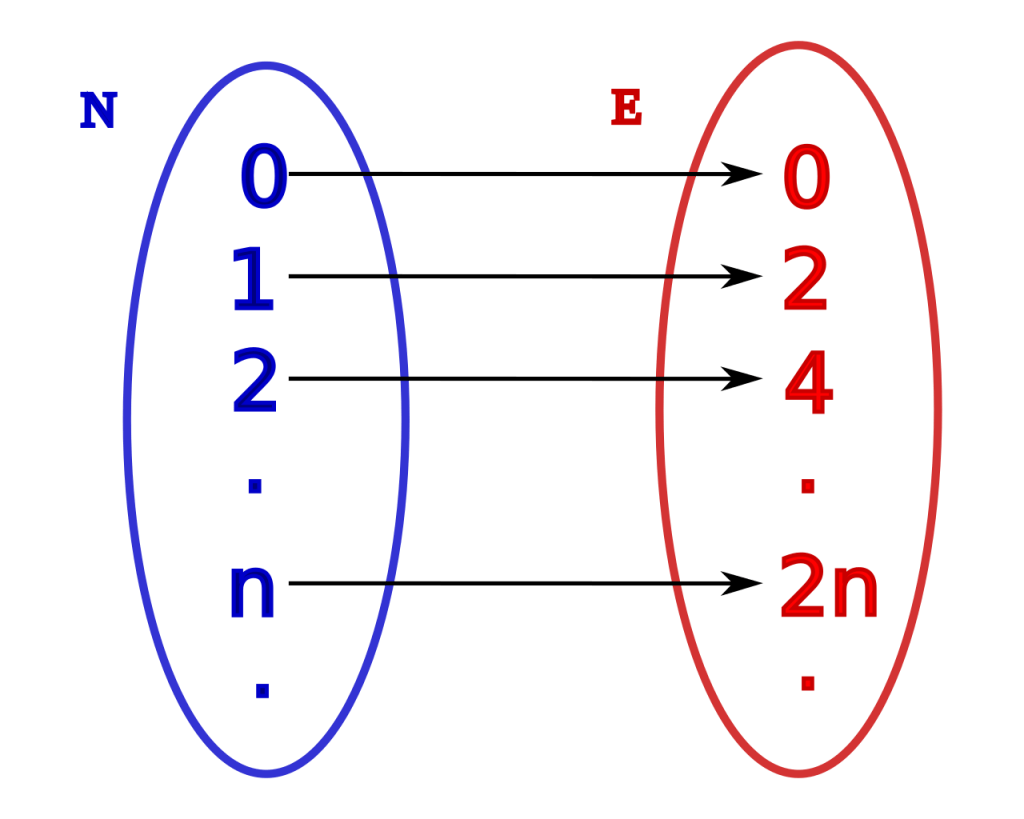

In order to understand Cantor’s idea of cardinality, consider two groups of numbers: the set of all whole numbers and the set of all even numbers. If I asked you how big the set of all whole numbers is compared to the set of all even numbers, I would expect you to say that it is double in size. This seems intuitive because, whilst both the sets of numbers are infinite, the even numbers appear half as frequently as the whole numbers when you count along the number line. And yet I can draw a one-to-one mapping of the whole numbers to the even numbers by pairing each whole number with the double of that number.

Pictured: A one-to-one mapping of the natural numbers N to the even numbers E. This illustrates that both sets have the same cardinality and so are ‘equivalent’ in size. Image taken from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cardinality.

This one-to-one mapping means that both sets of numbers are in fact the same size, which means they have the same cardinality. Infinity has now been repurposed to describe the size of any collection of objects and can now be used to compare relative sizes of infinity.

Cantor borrowed the Hebrew letter ‘aleph’ (ℵ) for the notation of his new version of infinity. The cardinalities of infinite sets are written as ‘aleph numbers’ with ‘aleph null’ (ℵ0) being the smallest. Sets with the same cardinality are known as ‘countable infinities.’ Any higher cardinalities are known as ‘uncountable infinities.’ This allows us to identify that the sets of integers and rational numbers are countable infinities, whilst the sets of irrational numbers and real numbers are uncountable infinities.

As mentioned earlier, Cantor was criticised by some mathematicians at the time but one staunchly came to his defence. David Hilbert (1862 – 1943) described Cantor’s work as “the finest product of mathematical genius” and exclaimed defiantly that “no-one shall expel us from the Paradise that Cantor has created.” Hilbert expressed Cantor’s work on infinity here in terms of the afterlife, a place of eternal happiness. Hilbert was himself agnostic but was raised Protestant. One might look at Hilbert’s words and think that infinity is not so much what it actually is but rather what you believe it to be.

So then, how does The Rings of Akhaten utilise this understanding of infinity during its climax?

We can divide the climax into two events: the Doctor’s speech that fails to resolve the situation and Clara’s speech that manages to succeed instead. The Doctor offers the Sun God his memories but this fails to satisfy its appetite. His passionate speech conjures up these incredible, awe-inspiring, seemingly impossible images of watching “universes freeze and creations burn” and “universes where the laws of physics were devised by the mind of a mad man.” The Doctor’s strategy here then appears to be to overload the Sun God with these extraordinary tales. But that’s a massive oversight on his part. A story is a story, no matter its length. Every story ends eventually. Even the Doctor realises this by The Time of The Doctor.

DOCTOR: Yeah, well, the sun’s gone down.

CLARA: Already?

DOCTOR: Everything ends, Clara. And sooner than you think.

The Doctor’s adventures may take on infinitely many forms but his memories are still finite in number. I think it’s also worth noting that throughout the entire story he is unwilling to sacrifice anything of his (his sonic screwdriver, Amy’s glasses, or even losing his actual memories). He is failing to understand the situation at hand here. But Clara Oswald gets it.

Clara doesn’t just offer her past memories but “a whole future that never happened.” She offers the uncountable possibility of all the future days she could have shared with her mother, “passed on to [her].” It would be impossible to map all the days that could have happened to the days Clara expected her mum to live out with her.

I would argue here that it’s entirely intuitive that she figures this out given that, unlike the Doctor, she has already made one sacrifice during the story. She sacrificed her mother’s ring, a circular object that symbolises a union that lasts forever, just to gain access to a space moped. Just like Hilbert proclaiming that Cantor had created a ‘Paradise’ from his work on infinity, it’s actually the sentiment of infinity that truly counts here. Clara is willing to offer the unbounded sentimental value she holds for her most treasured possession. That’s why she succeeds where the Doctor fails at the climax of The Rings of Akhaten.

But the Eleventh Doctor manages to learn from this failure. In The Time of the Doctor, he sacrifices the remainder of what he believes is his thirteenth and final life to defend the town of Christmas on the planet Trenzalore. And just like Clara’s sacrifice of “the most important leaf in human history,” it manages to change their future. I think that’s why we hear a reprise of The Long Song just before the Eleventh Doctor regenerates in The Time of the Doctor. He’s thinking about all his adventures, all of his memories. And he promises that he won’t forget one day. Perhaps that is why his story must end. Because infinity is just too much, even for his appetite.

>

Sources:

- Alex’s Adventures in Numberland by Alex Bellos.

- Things to Make and Do In The Fourth Dimension by Matt Parker.

- The Black Archive #42: The Rings of Akhaten by William Shaw.

Leave a comment